As Mark Twain once quipped (and the U.S. dollar’s dominant reserve currency status echoed): “The rumors of my death are greatly exaggerated.”

Investors have been handwringing about the end of the U.S. dollar’s status as the world’s dominant reserve currency for decades, yet the dollar has maintained its spot at the top of the reserve currency stack through these doubts and challenges.

The U.S. dollar has been the world’s principal reserve currency since the end of World War II and the establishment of the Bretton Woods monetary order. This dominant status has afforded the U.S. many incredible privileges including a more stable exchange rate, more liquid and lower cost borrowing, and an ability to influence global financial flows through actions like sanctions (there are drawbacks to having reserve currency status, such as a stronger exchange rate, which can be a headwind to exporters).

The U.S. dollar’s reserve status has persisted through many founded and unfounded bouts of fear about its dominance. The most notable founded bout was Nixon’s “shock” end to gold convertibility in 1971, which significantly devalued foreign dollar reserves but did not totally displace the USD as the world’s dominant reserve currency.

Though the U.S. dollar dominance has persisted, this is not to say there have not been changes in the U.S. dollar’s share of total global reserves. At its unsustainable peak in the early 1970s, the U.S. dollar made up over 80% of global reserves, it then preceded to fall to less than 50% by the early 1990s, then climbed back to over 70% in 2000, its most recent peak (for a fantastic visual of this, see this page from Visual Capitalist).

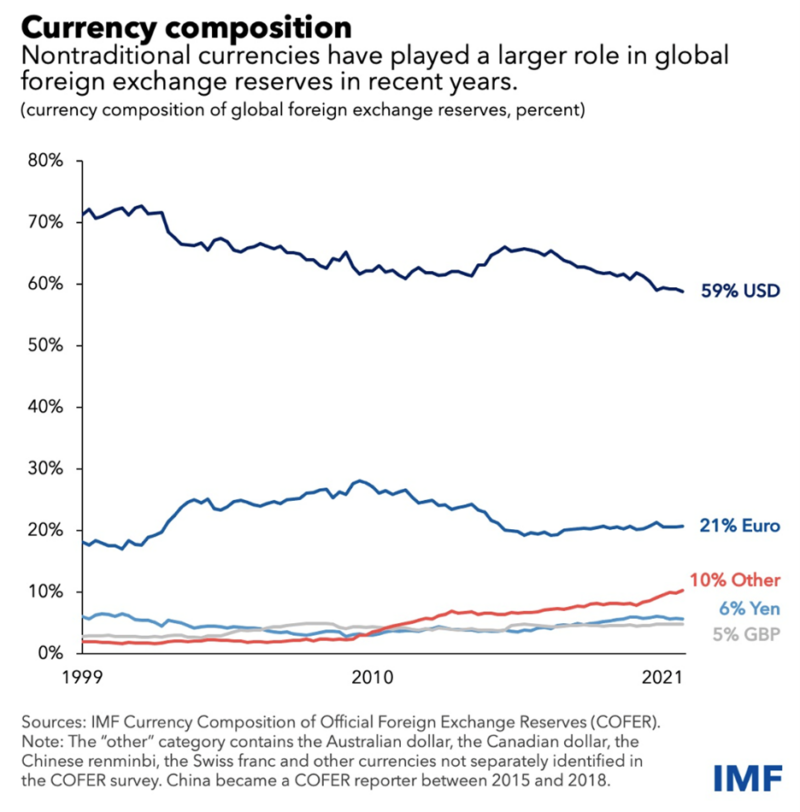

Since 2000, there has been a slow degradation in the share of U.S. reserves, as seen in the IMF chart below, but no other currency is anywhere close to the U.S. dollar’s sheer reserve dominance (note the most recent update from 3Q23 on reserve currency shares from the IMF still has the U.S. dollar at 59%).

It must be noted that in each of these time periods of expansion and contraction of the U.S. dollar’s share of reserves, the U.S. economy and financial markets experienced healthy growth (as well as recessions). The share of reserves has impacted financial markets, but it has not been the dominant driver of them (save for possibly in 2000-2006 when U.S. dollar weakness contributed to or was caused by sharp underperformance of U.S. financial assets compared to the rest of the world).

This isn’t to say that we should ignore the shifts in reserve weights, but to suggest that until there is “Clear and Present Danger” to the dominance of this status, shifts or slight erosions in reserves likely will not be the key driver of asset prices.

But just as Agent Jack Ryan does not grow complacent to shifts in his environment, neither should we.

Fears about further erosion of the U.S. dollar have been amplified in recent years following the far-reaching sanctions that the U.S. deployed in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

The U.S.’s aggressive use of sanctions has led some central banks (primarily Russia’s out of necessity) to reduce their reliance on U.S. dollar reserves. This has led to increased purchases of gold by central banks, as well as attempts to create “alternative financial infrastructures” (as defined in this great article by the Atlantic Council).

The reality is that central banks have been looking to diversify their dollar exposure and use for some time, long before the 2022 conflict.

In 2015, China created its Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) program, an attempted alternative to the U.S. SWIFT system (CIPS still uses some SWIFT functionality). CIPS was created to facilitate cross-border, bilateral trade priced in renminbi. In a simple example, this program has allowed China to buy some oil from Saudi Arabia priced in renminbi instead of having to transact in U.S. dollars. Though China has pursuits of “internationalizing” the renminbi, continued capital and currency controls has limited the adoption of the renminbi as a major reserve currency (the renminbi is just 2% of global reserves as of 3Q23).

Relatedly, the BRICS countries have been attempting to create a BRICS currency to facilitate trade between these large, emerging economies in their own national currencies instead of relying on the U.S. dollar. Though concerns about dollar reliance have been expressed for decades, progress has been slow, as outlined in this helpful Carnegie

Endowment report.

Fears about the U.S. dollar’s reserve currency status have also been amplified by swelling deficit spending as U.S. fiscal spending remains stimulative and interest expense consumes a greater portion of spending (interest expense has now exceeded defense spending).

This has sparked concerns that a “bond vigilante” or “Liz Truss” moment could occur in the U.S. Treasury market, where investors protest higher deficit spending by refusing to buy or demanding a higher yield on U.S. debt. The fall of 2023’s surge in the 10-year Treasury yield to nearly 5% ignited bond vigilante memories, but as Treasury yields have moderated, these fears have subsided. There, of course, could come a time where bond investors have less appetite for U.S. debt, making the funding of deficits more challenging and expensive. Though this time has been worried about for decades, it has yet to materialize.

So, as we look to the future and assess potential fears and challenges to U.S. dollar dominance, it is important to identify why the U.S. dollar remains so dominant as a reserve currency. These reasons include:

- It’s the Best (and Arguably Only) Option: TINA, there is no alternative, is true for currencies, with no clear better option for a different dominant global reserve currency. China has capital controls, Japan and the other Five Eyes Alliance countries are all too small (UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand), and the Euro is the second largest but considered relatively risky to the U.S. given the lack of a fiscal union. Currency baskets have often been floated as an alternative to U.S. trade flow dominance, however little progress has been made to their broad adoption.

- Reserve Currencies Are a Reflection of Geopolitics: History has shown that he who has the most guns has the reserve currency. With the currently undisputed dominance of U.S. military might, the USD’s reserve currency status remains. Major changes in reserve currency dominance have occurred around major wars or shifts in geopolitical dominance (such as the loss of the UK’s pound as the dominant reserve currency after World War II). Fears about the imminent loss of the U.S. dollar’s dominance would be more founded if the U.S. were to be engaged in a direct and

economy-engulfing conflict that could potentially threaten the current geopolitical order. If this were the case, we likely would have even greater concerns with which to contest. - Institutions Create Inertia: Global public and private institutions (the International Monetary Fund, banking systems, commodity trading, cross-border trading, and the list goes on) rely on the U.S. dollar and its unmatched liquidity and ubiquity to transact. This inertia has been a key reason why currency baskets have not gained significant transaction, as detailed in the Carnegie

Endowment report above.

These dynamics suggest that recent events (increased use of sanctions and desires to de-dollarize) could continue to cause an erosion of the share of the U.S. dollar in foreign reserves, however not enough to completely unseat the dollar as the dominant reserve currency. Overall, the U.S. dollar remains the world’s dominant reserve currency for many solid, entrenched reasons, though shifts in the share of reserves are bound to occur.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

The views and opinions included in these materials belong to their author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of NewEdge Wealth, LLC.

This information is general in nature and has been prepared solely for informational and educational purposes and does not constitute an offer or a recommendation to buy or sell any particular security or to adopt any specific investment strategy.

NewEdge and its affiliates do not render advice on legal, tax and/or tax accounting matters. You should consult your personal tax and/or legal advisor to learn about any potential tax or other implications that may result from acting on a particular recommendation.

The trademarks and service marks contained herein are the property of their respective owners. Unless otherwise specifically indicated, all information with respect to any third party not affiliated with NewEdge has been provided by, and is the sole responsibility of, such third party and has not been independently verified by NewEdge, its affiliates or any other independent third party. No representation is given with respect to its accuracy or completeness, and such information and opinions may change without notice.

Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Any forward-looking statements or forecasts are based on assumptions and actual results are expected to vary from any such statements or forecasts. No assurance can be given that investment objectives or target returns will be achieved. Future returns may be higher or lower than the estimates presented herein.

An investment cannot be made directly in an index. Indices are unmanaged and have no fees or expenses. You can obtain information about many indices online at a variety of sources including: https://www.sec.gov/answers/indices.htm

All data is subject to change without notice.

© 2024 NewEdge Wealth, LLC